Possible triggers: sexual violence and assault.

Game developer Brianna Wu of Giant Spacekat recently wrote a an essay that started as an examination of a game-of-the-year podcast and became a critique of gaming podcasts in general, an essay demonstrating how the dominant paradigm in gaming journalism — typically straight, white, male writers — reflects the continued dire marginalization of women in gaming, as characters, as gamers, and as audience. As I read, I found myself nodding repeatedly; though I am not a big podcast listener, I was nodding because none of this is new. Because I’ve heard it all before. We all have.

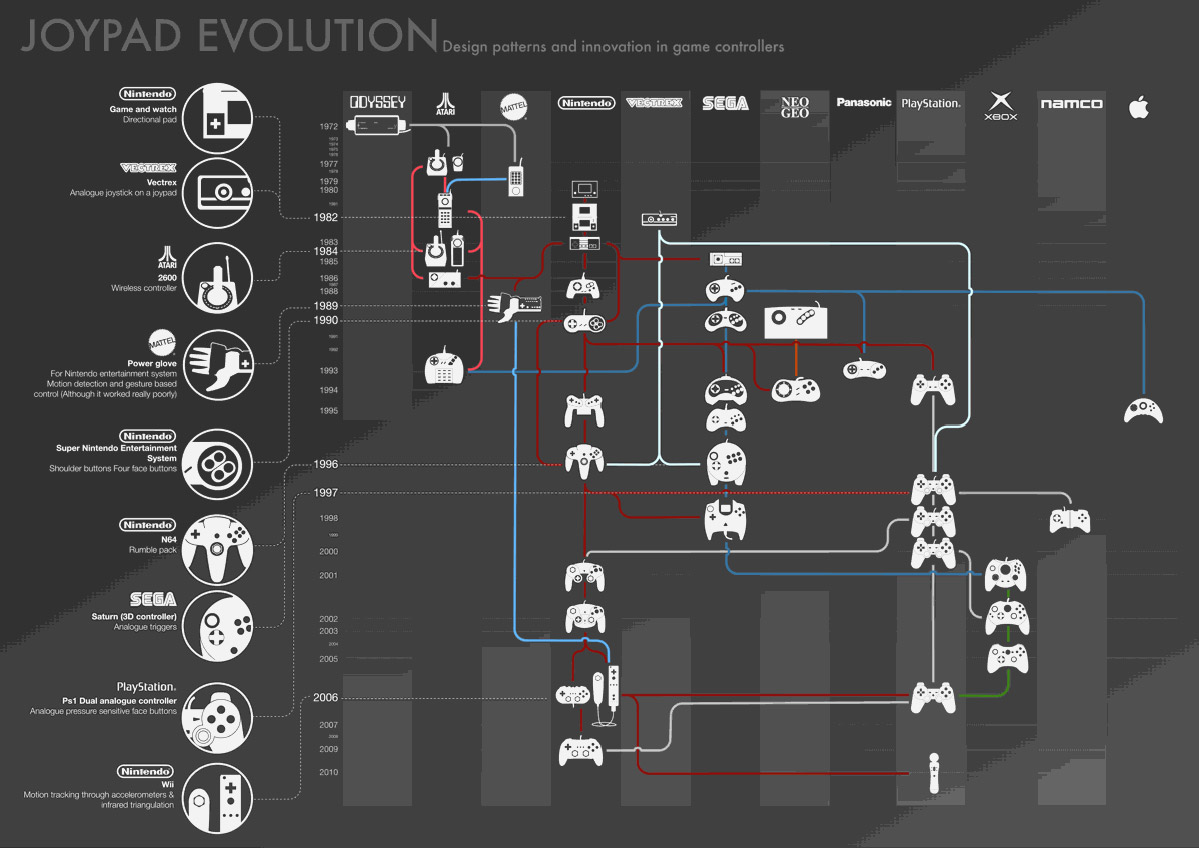

Here we are, at the beginning of a new year and a new generation of mainstream superheroes and comic geekery, new gaming consoles–yet in gaming, and indeed much of geek culture, women are still treated as second class citizens. Yes, I agreed with Wu’s take on male-dominated podcasts when she pointed out they weren’t much interested in either gender issues or female leads. But I fear the issue is even worse than we often grant. After the events of the last few years, when social media rampages against women in the games industry have become so rampant, after campaigns against strong female representation have reigned supreme, and when female leads in games continue to be shunted aside, either in favor of tired, repeated tropes or as victims of so-called subpar game design, it seems to me that it’s time to call the match: we’re not welcome here. After all these years, after all our efforts, we are still not welcome in the boys’ club of geek culture.

This, for me, is a hard idea to swallow. I’ve been heavily involved in geek culture since the mid-’90s, when I regularly played Magic: The Gathering and spent my days playing video games and watching anime. I skirted comics, never getting heavily involved, but reading a few selected titles religiously. I followed geek-friendly shows and movies. Even as I began to skew more toward literary fiction, a good third of my personal library was, and still is, dedicated to science fiction and fantasy. I came of age as a geek before geeks were cool, and I’ve stayed here ever since. And yet, in this twenty-year span, which includes a stint writing for a major gaming website, I have never felt fully welcome, wanted, or accepted outside of a close circle of friends, simply because I am a woman.

This is the point in a narrative like this at which someone cries out, “That’s anecdotal! That’s just your experience!” Of course it is. It’s my personal story. But I’m not alone in this. Stories of women in the games industry, for example, continually reflect this culture of exclusion. Not only have we documented many stories here, but the hashtag #1reasonwhy continues to go strong on Twitter, after more than a year. One reason why what? Why more women aren’t involved with gaming. Kotaku’s Luke Plunkett compiled a list of some of the then-best tweets back in late 2012, and that post serves as the tiniest of glimpses into what we talk about, and experience, every day.

Plunkett called the tweets “devastating.” Perhaps not as devastating as the comments on his post, though.

Anecdotal is what came up in the comments, too, when Polygon’s Tracey Lien wrote a brilliant look at how, exactly, the exclusion of women from the world of gaming came about. Lien built much of her article from interviews, talking with people who had been in the industry for decades, as well as individuals involved in marketing and other related fields. Polygon’s Russ Pitts penned a piece on the history of Xbox Live in a similar style, but no one cried “anecdotes.” A feature on California arcades. On what makes a successful Kickstarter. On games in the traditional English classroom. All features written by men, in the same style, making connections in similar ways — and yet the research and interviews are not challenged in the same way.

Anita Sarkeesian, too, relies on anecdotal evidence, apparently.

The anecdotal attack is a common one in the fractious world of online discourse, but it seems to be employed much more commonly when articles are written by women, or when the stories presented are stories about women. It’s a tool used to undermine women in the industry, from the journalists who happen to be women to the industry vets who complain about instances of sexism and sexual assault. It’s all just anecdotal, despite documented and lengthy cases of harassment, undermining, and even threats.

And we’ve all heard the “stop talking about it, and it’ll go away” message from those who think not sharing our stories is a good way to end sexism (see the comments here on Leigh Alexander’s column for a great example). We’ve been told that sexism and objectification doesn’t hurt anyone, so we should shut up with our complaints. Our discourse isn’t welcome. Our stories are not welcome. Writers who frequently engage on issues of race and gender will often say that the best thing members of the dominant group or groups can do is simply listen.

No one wants to listen to us. Not when we’re being harassed, like Jennifer Hepler. Not when we’re pointing out how an industry based in equality turned into a boys’ club, like Tracey Lien did in her Polygon feature. Not when we’re pointing out that creating and supporting rape culture is a bad idea, even when it springs from a joke, though Gabe did finally, seemingly sincerely, address the Penny Arcade Dickwolf controversy twice recently (the second time a few days ago), but it took years for people to simply listen. Only time will tell if anyone was heard.

We could cast the cultural net wider. 2013 saw blogs, forums, Facebook fan pages and groups and more dedicated to violent outbursts against female characters. Women on Game of Thrones, Breaking Bad, and The Walking Dead were targeted with hatred from the fringes of their various fandoms. While sometimes the critics merely called for these characters to be killed off, at other times the outrage reached more violent, extreme reactions stretched to calling for characters to be raped and tortured. Some of this is so vile, I won’t even link examples. I’m sorry. Instead, it’s interesting to explore how other characters from those same shows — male characters — are treated in the fandom. All three of these shows have something in common: they are peopled with characters who make mistakes that often stem from terrible decisions. In fact, one might say that nearly all the characters in these shows have done terrible things at some point, and yet, with the exception of Game of Thrones’ Joffrey, rarely do we see the sort of violent reaction to the men that we do to the women. Jaime Lannister’s first real memorable act in Martin’s books, and in the show, is to throw a young boy out of a window, and I can’t recall every stumbling across anyone saying he should be raped and tortured, and then his head put on a spike, but I’ve seen this call for Catelyn Stark so many times I’ve begun avoiding several sites. Fan discussions simply aren’t worth it.

But this was also the year that saw new lows when a superhero show was cancelled because no one wanted a female audience, and the ponies of Equestria became fun-and-fashion-loving teens in short skirts.  And let’s not even talk about the Powerpuff Girls.

And let’s not even talk about the Powerpuff Girls.

Banner year.

But there were a few highlights. For example, movies with women who actually had conversations that weren’t about men made more money than those that didn’t. Downside? A distinct lack of female directors, but hey, a successful year for the Bechdel test is a step in the right direction. 2013 also saw several (several!) strong female characters in games, many of whom took lead roles. But what happens when those games aren’t commercial or critical successes? When the cast of the Giant Bomb podcast won’t even talk about a grittier, more realistic Tomb Raider as a contender? What happens next year, or the year after, in terms of female heroines?

And just think, y’all: 2013 was supposedly a good year for women in games.