A couple of weeks ago I promised that I would post the talk that I gave on games and bioethics at RSA. Now I have finally gotten around to doing it! What follows is (loosely) the text of my talk along with the slides from my presentation which have been strategically placed. I have not included the video clips that I used during the talk but they are adequately described. Be aware that those descriptions do contain spoilers, but I warn you at the beginning of the paragraph so that you can skip it if you like. Enjoy!

While it has not been unusual for society at large to ignore the unethical nature of many 20th century medical “breakthroughs” many of them have come under scrutiny in a variety of media. While the 1932-1972 the Tuskegee Syphilis experiments allowed numerous untreated African Americans to die from untreated syphilis, despite there being a cure for the disease, at the behest of the US government which never disclosed that they were infected with the disease and allowed them to think that they were receiving government funded treatment for a generic malaise regionally called “bad blood”. The study was terminated in 1972 after the details study were leaked to the press. At that point only 127 of the original patients (and I don’t call them subjects because they were not aware that they were being experimented upon) were still alive.

1997 saw the release of the critically acclaimed film, Miss Evers’ Boys which detailed the lives and deaths of the victims of the Tuskegee Experiment. In this same year the government issued its first apology (delivered by President Bill Clinton) for its role in the atrocity.

While Miss Evers’ boys won Emmy and Golden Globe awards, the made for tv movie and Clinton’s apology probably created what my daughter would call “tiny buzz” at best. If I ask my undergraduate students today, most of them still have little to no knowledge about these experiments or knowledge of the fact that they were conducted on a population in order to see how African Americans “responded” to the disease when there was actually a cure for it and not to find a cure for the disease itself. And then we have these little beauties.

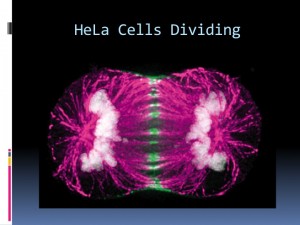

The immortal HeLa cells. Cervical cancer cells that were harvested from a cancerous tumor found on the cervix of a young African American woman named Henrietta Lacks on February 1, 1951.

Mrs. Lacks was not mentioned. The HeLa cells went of to help develop a polio vaccine, study various forms of cancer in labs around the world, as well as to study the effects of the parvo virus on dogs and cats. The Lacks family did not discover the existence of the HeLa cells until serendipitously one of Henrietta daughter-in-laws met a lab researcher at a friend’s house in 1975 (more than two decades after Henrietta’s death) who recognized her surname and told her that she had been working with HeLa cells in the lab. When Rebecca Skloot found the family of Henrietta Lacks, largely impoverished and mostly without medical insurance themselves and completely uninformed about the status of their mother’s cells.

When Skloot’s 2010 book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks was published I asked several of my MD friends about Lacks and while they were well aware of HeLa cells, none of them could recall reading anything about Henrietta Lacks herself.

It wasn’t until the publication of Skloot’s book and until a number of colleges and universities across the country picked up the book for their Common Read book for incoming freshman (which for most also included a number of activities surrounding the book, including a lecture and Q&A with Skloot) that students even learned about HeLa and began to ask bioethics questions. It was through the more communal and interactive activities that the world of Henrietta Lacks and (medical) ethics have began to unfold. It is the time that the humanities and the hard sciences are beginning to play well together for these students and they begin to see the import and recognize that there are humans behind the lab equipment (and it’s not just the folks running the experiments).

Interactivity .

That is key. In recent years cognitive studies of interaction and pedagogy have taught us nothing if they haven’t taught us that people learn better when there is a certain degree of interactivity

…when they are engaged.

Ironically, bioethics is an issue that has come to the fore in a number of AAA titled video games. Today I want to take a quick look at two in particular. 2010 saw the release of Bioware’s Mass Effect 2 in which the lead character, Commander Shephard is killed when she (or he depending on the players customizations) is sucked out into space after the destruction of her ship.

Shephard is brought back to life by the Lazarus Project that is funded by a mercenary organization that she has fought against as a soldier of the Alliance. After her revival (and augmentation) she finds herself in the situation of being forced to work with the organization in order to save the universe from destruction by mechanical aliens of sort. All choice is taken from Shephard (and the player) because she is sure (and assured by many) that as one who has been revived and augmented by the bad guys and is now less trusted by association. ME3 Spoilers (if you don’t want to hear this plug your ears and close your eyes for the next 2 mins or so). In the follow up ME3, which ends the trilogy that began in 2007, the game ends with Shephard having to ultimately decide if she will make the choice that will destroy the Reapers (the aforementioned aliens) and all synthetic beings in order to save the universe (and it is implied that she will be included because of the augmentations that were done without her permission back in ME2), attempt to control them (and die), or merge herself with the alien.

Here gamers are asked to make a decision about not only the future of the universe but the life or death of the character that they have been playing for the last 5 years (characters are imported from previous iterations of the game). There is huge buy-in, there is investment on top of the interactivity. And a lot of the final decision is influenced by the fact that Shephard’s synthetics were implanted without her knowledge or permission. The issue of medical ethics hits home in a huge way.

When I first proposed this paper, I thought that I would be using Eidos/Square Enix’s 2011 game Deus Ex: Human Revolution because it has many of the same narrative elements as ME. In Deus Ex, the male protagonist is mortally injured while on duty and is brought back with a series of cybernetic augmentations. Throughout the game the protagonist, Adam Jensen, constantly reminds the players and all of the supporting characters that he indeed “didn’t ask for this”. By the time it came time to write this paper, I had experienced ME3. And I say experienced because it felt more like experiencing it than playing it by the time we got to the third and final installment and this game had resonated with me more than any game before. I felt connected to Commander Shephard (specifically a FemShep) in ways that I had never felt connected before. Not even to MMORPG characters that I had played for years. The decisions that I had made as her made her more me than I had ever experienced before. And the hubbub that arose in the gaming community after the end of the game only proved to me that I was not the only player who felt this way. Players were ultimately dissatisfied with the ending of the game because they felt that while the choices that they had made throughout all 3 iterations of the game (up until the very end) their choices had guided the narrative and that they had indeed determined the fate of Commander Shephard (and numerous races of beings), but that the ending choices were not representative of the distinct choices that their characters had made throughout. Ian Bogost would see this as a break down in the interactivity of the game. The level of interactivity had been such and maintained in such a way for all 3 games that player buy-in to Commander Shephard as a being (or the player herself) was extraordinarily high. In Persuasive Games Bogost writes,

While for Bogost to a lesser extent in procedural rhetoric in Persuasive Games and to a greater extent in OOO in Alien Phenomenology ethics and the code are inextricable in a posthuman way because the code and the environment that it creates is all that really is. We as gamers, players, and experiencers are merely button mashers and our button mashing is not a “sufficient cause for agency, genuine embodied participation in the environment”. All the world’s a stage, we’re just button mashers.

While I may (and do) disagree vehemently with some of what Bogost says I think that he is spot on with some of his notions how environments are created and what they do. What he leaves out for me is the Body of, in, and around the code. For me, this is the human element that programs, experiences, interprets, and is represented by the code. It is within that body—that embodiment— and it’s relationship with the code and what it can create that the real ethical discussion and understanding comes about.

For Bogost the code is the central thing and has equal value to all other thing organic and not. But for me code and the environment that it can create are all like that tree it the forest. If code builds procedural and participatory (aka interactive) environment and there is no human there to interact with it does it still exist? Like the sound of the falling tree that needs the intricacies of the human auditory system in or to exist..to be heard, the code needs the human in order to be interactive, to be interpreted, to be experienced as ethical, or not.

2 thoughts on ““I Didn’t ask for this”: On (Bio)ethics, Rhetoric, and Video Games”

Nice post Sam. When reading the Skloot book in our RhetorEthics class we kept bringing up one specific anecdote when discussing ethics and the human body (paraphrased)–researchers now don’t trust HeLA cells specifically because they’re so far out of the realm of “normal” cancerous cells on account of their quick and drastic mutation.

When I went to this Chicano Studies conference last year, I watched a documentary screening/panel that focused on Mission, Tx. (where I went to High School). Up until the mid-60’s Dow, along with several other private and federally funded companies, had a plant that produced (among other things) Agent Orange, mustard gas, pesticides, etc. This factory was in the middle of a residential neighborhood, literally across the street from a school. There were interviews with (now deceased) adults who were children at the time–they described “rainbow” rivers where, after raining, they would play in the semi-flooded streets and watch as the chemically laden water would reflect a rainbow. They talked about playing in piles of “powder” just laying out in the parking lot of the plant. The infant mortality rate skyrocketed, and generations of families are suffering from drastic health defects. Oh and what happened to the plant after it closed? The company moved its operations to Bhopal, India. Yeah…

This and numerous other experiments that you’ve talked about, specifically with impoverished women in Latin America, make me wonder: why is the burden of proof placed on the subject? Is it because he/she lacks the social capital of an M.D? Is it the media’s unwillingness? Or is it fear of being stifled by government entities that keeps word from getting out.

I’d type more, but this is all aggravating me right now and I need to teach in less than an hour…

I didn’t even get into the “heroization” of the early eugenics project that they called”The Pill”. They tested the early iterations on women “below the border” (ie your folks ‘Tacious) and, of course, claimed that the deaths of any of the test subjects had nothing to do with their use of the pill.

We could also consider other cases of environmental racism….can you say above ground power lines in poor communities? Nothing like whole neighborhoods full of kids with leukemia when there is no family history. But this is shit you rarely hear about and when you do the politicians and lobbyists come in and accuse us all of wearing tinfoil hats.